For a week now we have been reflecting on a magical day for Middleton Stoney Cricket Club, when we beat the formidable Melbourne Cricket Club XXIX. Today, however, is one of the most challenging days in any season, when I have to notify the club of our selections for the last matches. Other skippers seem to take this in their stride but I find selection difficult.

Our players are asked to let us know their availability by the 15th of the preceding month, then we try to let them know as soon as possible who is in the team for which games. I send an email at the end of each week bringing club members up to date on match reports, tweets, team lists and other club news, so I should let everyone know this evening the selections for our remaining games.

Twenty-six players have declared themselves available, many for all four of our September matches. Mathematicians will have worked out, however, that not all of them can even play two of our last four games. So the monthly selection round is a constant disappointment.

It is especially problematic because we do not select on ability (thank goodness, in my case) but with an attempt to balance our strength with the opposition’s for each Sunday and with the intention of being fair between our members. But what is fair? That is the perennial question in my day job as a legal philosopher but it is quite a challenge to apply any answer in a small community such as a friendly village cricket club. Should we hold it against X or Y or Z that they have withdrawn at the last minute in previous months? Should we take into account that some play for other clubs in league cricket? When, if ever, should we choose our best team, even if we knew what that might be?

Obviously, there are some parallels to Test cricket here and some differences. For instance, whether or not players are really fit is a shared concern but the selectors of Test teams probably do not place as much weight as we do on whether contenders have discharged their tea-making, barbecue-running and subscription-paying duties, let alone whether they have taken their turns as umpire or scorer or boundary flag collector.

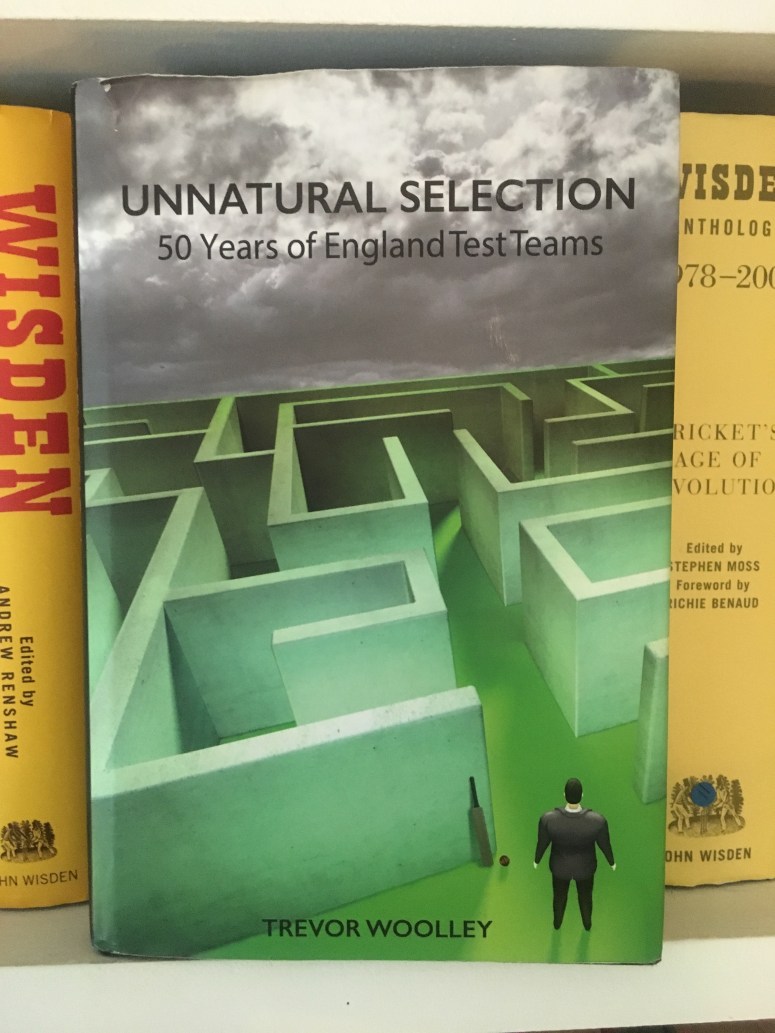

So I have been studying the most detailed book I have found on cricket selection, Trevor Woolley’s Unnatural Selection: 50 Years of England Test Teams (Von Krumm Publishing, 2015). Woolley argues that, ‘for all that has changed over 50 years, the principles of picking a cricket team have remained the same. There is a need for a captain to lead the team – perhaps drawn from among the best available 11 players, perhaps from beyond. The team needs to be balanced – ideally five batsmen, four bowlers, an all-rounder and a wicket-keeper.’

That is at Test level. At our level, everyone bar me seems to be an all-rounder and we have lots of wicket-keepers, as indeed do England. Writing in 2014, Woolley declares that, ‘The perception that a team cannot be great without a genuine all-rounder is simply a fallacy. Neither of the great sides of recent years had one …’ He is referring to the West Indies teams led by Viv Richards and the Australians led by Steve Waugh although both of those captains would count as all-rounders at Middleton Stoney. See, for instance,

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RS703gGoq6Q

Middleton Stoney batsmen who bowl, or bowlers who bat, or batsmen who bowl but who also like to keep wicket, are not that bothered about whether they are genuine all-rounders so much as whether they have a chance to develop all their talents. This happens in the field where the ball seems to follow those who are slightly weaker in this aspect of the game, wherever the captain places them. In batting and bowling, however, players need the skipper to give them the opportunity.

Even getting on to the field is a challenge when twenty-six people want to play in our XI but as many can only play once a month in the rest of the summer, we need that many members to cover earlier fixtures.

In wider life, selection issues are equally crucial. In university appointments and deployments, for example, there are almost always more qualified and eager candidates than there are positions.

We are good, we think, at second-guessing national selectors of world cup squads in cricket, rugby, football, netball and other sports, if not at reflecting on our own mistakes or successes. But Woolley’s book is not about telling selectors, with the benefit of hindsight, why they were allegedly wrong. It is instead a detailed attempt to understand why the selectors made the decisions which they took.

Many of us, if not selected for a team or a job or a role, might cast ourselves as a Danny Cipriani, rugby union players’ (and journalists’) player of the year but not selected for the England World Cup squad. Few of us have the strength of character or resilience to react in the way Cipriani has:

As always when listing our selections, I trust that disappointed team-mates will show such grace, forgive my mistakes and seize any opportunities that do come their way to make us re-think the assumptions underlying our selections.